Trans Inmate Transfers out of Women's Prison

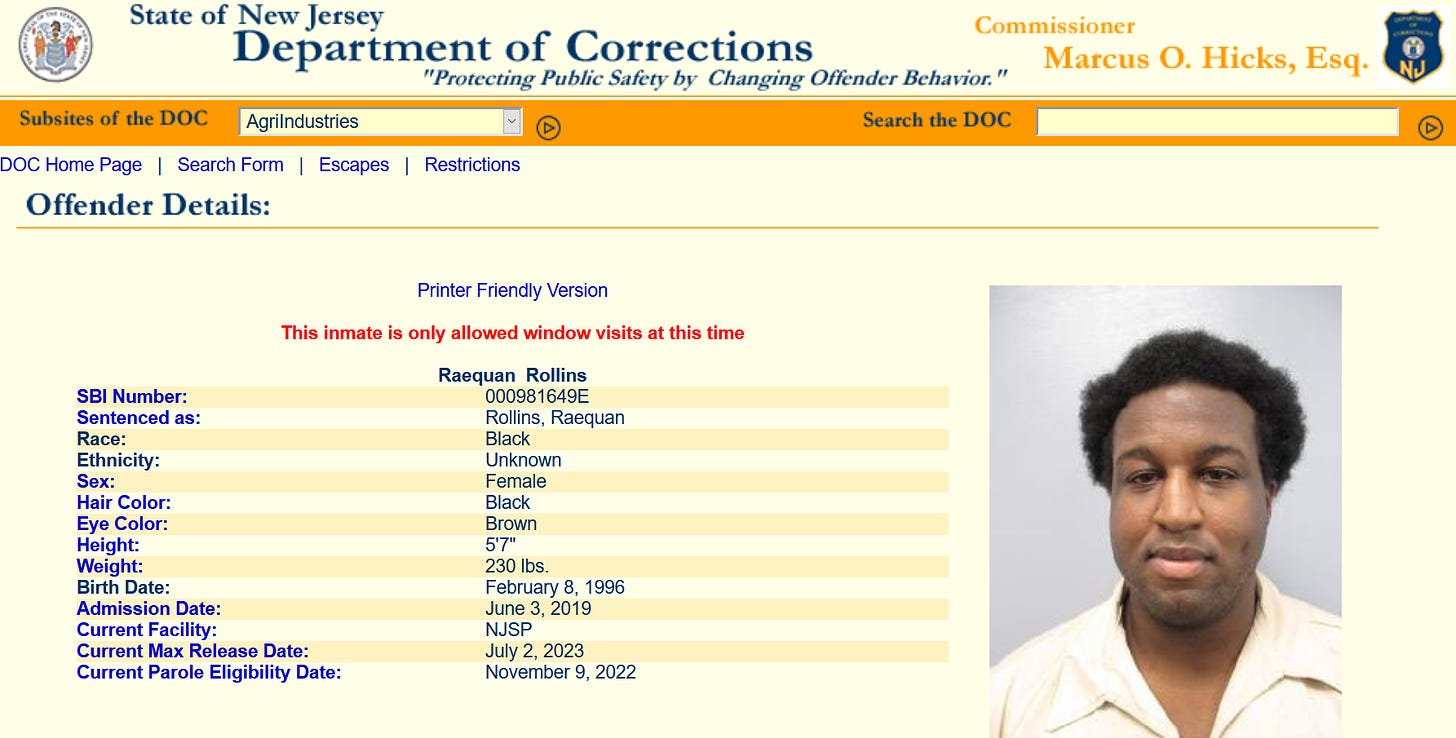

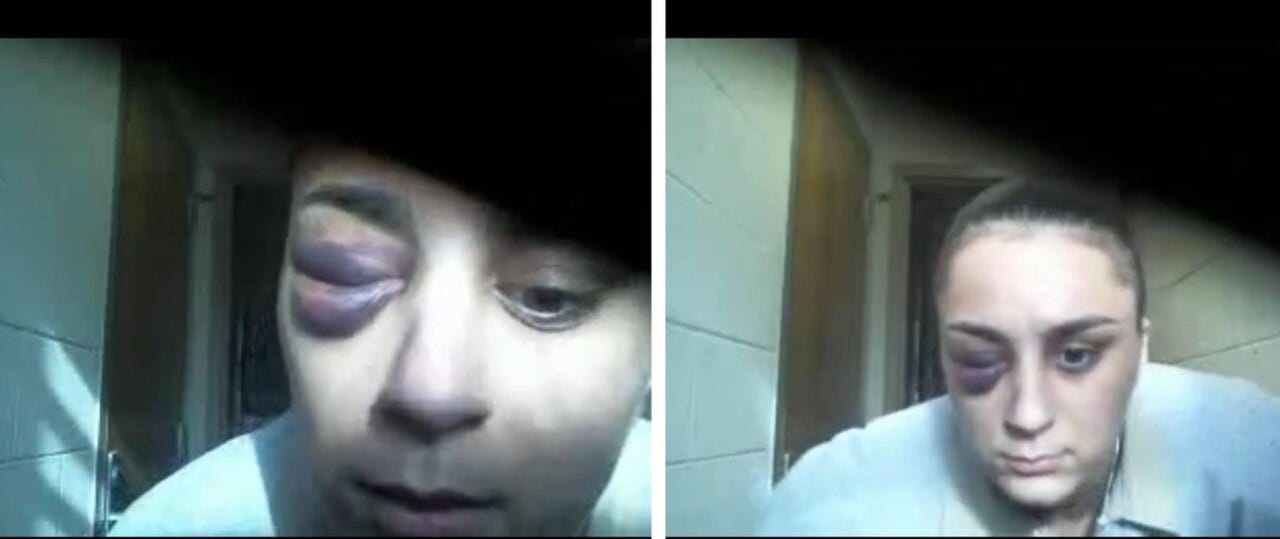

Systemic abuse in women's prison caused him to feel 'unsafe'

‘Rae’ (Raequan) Rollins, a trans-identified male convicted of robbery who was transferred to a New Jersey women’s prison, has returned to a men’s facility after being abused by male prison guards. On January 11, in the Edna Mahan Correctional Facility for Women, Rollins was handcuffed and beaten by prison officers along with at least two women. In a lawsuit filed by Rollins in March, he claims he was punched and kicked, resulting in injury to his legs that required the temporary use of a wheelchair. One of the women also assaulted, Desiree Dasilva, was hospitalized with a broken orbital bone. Another woman alleges she was punched in the head 28 times while pressed face-first against the wall. Inmate Ajila Nelson says a group of officers beat and punched her, stripped off her clothes, and one male officer grabbed her breast and put his “fingers into my vagina.”

According to local press, during what ought to have been routine “cell extractions” conducted to search for contraband, the officers wore riot gear, carried pepper spray canisters and shields, and moved in formations of five from cell to cell. Inmates believe it was a coordinated attack, and this claim is supported by documented evidence of abuse at Edna Mahan Correctional Facility for Women that spans decades.

A report released by the Department of Justice in April 2020 detailed shocking instances of violence by staff against women inmates in what was described as a ‘pattern’ of abuse. The DOJ report stated that the corrections department “fails to keep prisoners at Edna Mahan safe from sexual abuse by staff,” and “Edna Mahan suffers from a ‘culture of acceptance’ of sexual abuse, which has enabled abuse to persist despite years of notice and efforts towards change at the state level.” Over the course of the investigation, federal officers reviewed 70 reports of staff-on-prisoner sexual harassment and abuse over “several years” and called substantiated cases “varied and disturbing.” During a period dating from October 2016 to April 2019, seven corrections officers and one civilian employee were arrested, indicted, convicted, or pled guilty to charges related to sexual abuse of the prisoners they were assigned to supervise. Senior officers who had worked at Edna Mahan for years were involved in many instances, and multiple victims were identified.

In 2016, a vocational instructor was sentenced to three years for bribing two inmates for sex with smuggled cigarettes. In 2017, four officers pled guilty to charges of sexual abuse, including one corrections officer tasked with instructing new hires that sexual contact between officers and inmates was a criminal offense. He was sentenced to three years in prison. One corrections officer was found guilty of five counts of sexually abusing prisoners and sentenced to 16 years in prison in May 2018; the officer raped women by threatening them with disciplinary action if they failed to comply.

In addition, the report details testimonies from dozens of prisoners who describe being watched while undressing or being made to undress, as well as being strip searched in front of groups of male officers. Women state that officers routinely referred to prisoners as “b-tches,” “hoes,” “a--holes,”“d-ke,” “stripper,” “fa--ot-a--ed b-tch,”“motherf-ckers,” and “whores.” In still other instances, staff required prisoners to undress, masturbate, even engage in sexual acts with other inmates, while staff watched.

Despite the abuse against women continuing for decades and over 70 reports of staff-on-prisoner violations, the DoJ found that “Edna Mahan have been aware that their women prisoners face a substantial risk of serious harm from sexual abuse, and they have failed to remedy this constitutional violation.” For example, a 1999 lawsuit filed by two women suing the then-state corrections commissioner, superintendent and a corrections officer cited 10 incidents and stated that Edna Mahan administration was aware of such occurrences since 1990. The case was dismissed, and during an appeal the court agreed with the dismissal, and found that the administration could not be held liable for failing to protect inmates from a substantial risk of harm.

However, swift action was taken following news of the abuse of trans-identified inmate Rollins and his subsequent lawsuit. Mainstream media outlets reported how “prison guards kicked and punched a transgender woman” while the history of violence against women at Edna Mahan was often mentioned in passing, as an aside from the main narrative of discrimination against trans-identifying men. Trimeka Rollins, Raequan’s mother, told The New York Times how he had been shuffled from one men’s prison to another before transferring to Edna Mahan, only to find that conditions at the women’s prison were worse than at facilities for male offenders. In response to the attack on Rollins, 31 guards were suspended within the month, including the prison’s top administrator, 22 correctional officers and nine supervisors, and a formal investigation was opened. NJ Spotlight News reports of upcoming reforms, including body cameras for prison staff, an overhaul of policies, and employee training sessions.

In May, it was reported that Rollins has been transferred from Edna Mahan Correctional Facility for Women to New Jersey State Prison in Trenton. Rollins is listed in public records as "female", yet retains the privilege to identify as a woman, bypass sex-based protections for female inmates, and then to transfer out after experiencing a fraction of the violence meted out to women. Significantly, his suffering has been taken seriously by policy-makers while the systemic rape and abuse of women went ignored for decades.

Across the US, women are raped, assaulted, strip searched, or otherwise violated by prison officials — often by male officers. This is a reality that women cannot escape by declaring themselves to be something other than female. In 2019, Los Angeles’ Lynwood women’s prison was ordered to pay $53 million in compensation to more than 93,000 women who were strip-searched in a deliberately dehumanizing manner between 2008 and 2015. Several other lawsuits lodged against Lynwood allege rape and sexual violence, including a 2019 settlement for $950,000 for a former Lynwood prisoner who claimed that she was sexually assaulted by a deputy while inside.

A pattern of degrading strip searches in the presence of male officers, as well as legal action by women alleging sexual abuse, has also been recorded in Chowchilla’s Women’s Facility in California, Logan Correctional Center in Illinois (where a trans-identifying male inmate was also accused of rape), Wayne County jail in Michigan, Coleman Federal Correctional Complex in Florida, and Chittenden Correctional facility in Vermont. These cases are in clear violation of women’s 4th Amendment rights, wherein a prisoner has the right “to shield . . . [her] unclothed figure from [the] view of strangers, and particularly strangers of the opposite sex.” In regards to systemic abuse in women’s prisons across the US, in many instances women described retaliation against them for speaking out and were discouraged from filing complaints, indicating that the scale of the problem is far larger than is currently known. Sexual assault is universally underreported due to a fear of retaliation or of being disbelieved, both inside and outside of correctional facilities.

Moreover, a majority of women incarcerated in US jails and prisons are themselves survivors of sexual or physical trauma, or both. According to a 2016 report from the Vera Institute of Justice, 86 percent of incarcerated women have a history of abuse; 77 percent have a history of intimate partner violence; this, in turn, contributes to high rates of post-traumatic stress disorder, leading women’s rights advocates to describe this phenomenon as a “sexual abuse-to-prison pipeline”, only for survivors to be re-traumatized in a confined environment, with no escape.

Rollins’ case emphasizes how men who appropriate womanhood are able to opt out of women’s sex-based oppression and highlights the need for women’s prisons to exclude all men, even as employees, in order to protect vulnerable women from male sexual violence. This is an opportunity to remember why women need spaces free from men who would otherwise exploit them, and to demand expansions to such protections — even while pushing back against powerful forces intent on stripping away women’s rights to dignity, privacy, and safety.

Addendum

While researching incidents of sexual violence in women’s prisons, I came across many more instances of male staff-on-inmate violations than those listed above and have provided further evidence here:

Alabama

Tutwiler Prison for Women (systemic sexual abuse)Alaska

Cordova Center ($1.4 Million awarded to raped Alaska women prisoners)Arizona

Perryville Prison (harassment, assault, rape)California

Chowchilla Women’s Facility (systemic sexual abuse)Colorado

Denver Women’s Correctional Facility (attempted pimping)Connecticut

York Correctional Institution (sexual assault)Delaware

Baylor Women’s Correctional Institution (systemic abuse and assault)Florida

Coleman Federal Correctional Complex (systemic abuse and assault)

Lowell Correctional Institution (systemic abuse and assault)Georgia

Emanual Women’s Facility (prison supervisor raped inmates)

Women’s Correctional Institution (class-action lawsuit of 200; pimping, creation of pornography, systemic abuse and assault)Hawaii

Women’s Community Correctional Center (systemic abuse and assault)Idaho

Department of Corrections (rape by a supervisor)Illinois

Logan Correctional Center (violent strip searches, systemic abuse, rape by trans-identified male inmate)Iowa

Mitchellville Correctional Institute for Women (sexual misconduct)Kansas

Topeka Women’s Correctional Facility (systemic abuse and assault)Kentucky

Larue County Detention Center ($1.1 million settlement, systemic abuse and assault)

Lexington FMC (rape by male employee)Louisiana

Jefferson Davis Parish jail (deputies pimped women)Maine

State Prison (repeated assault by an officer, $1.1 million settlement)Maryland

State Correctional Institution for Women (Second-highest rate of systemic sexual abuse in the nation; female inmates abused more than male inmates)Massachusetts

Suffolk County & Framingham facilities (rape by guards, sex-for-drugs rings)Michigan

Wayne County jail (mass strip searches in front of male guards)Minnesota

State Department of Corrections (sexual assault)

Shakopee Women’s Prison (several instances of sexual assault)Missouri

Chillicothe Correctional Center (repeated rape, systemic sexual abuse)Montana

Montana Women’s Prison (systemic rape and abuse)Nevada

Southern Nevada Women’s Correctional Center attempted unsuccessfully to ban men from holding supervisor positionsNew Hampshire

Shea Farm Halfway House ($1.9 million class-action lawsuit for rape)New Mexico

State Corrections Department (officials knowingly allowed male staff to sexually abuse women)New York

Metropolitan Detention Center (systemic rape and assault)

Albion, BHCF, Lakeview, & Taconic facilities (class-action lawsuit against four prisons over systemic rape)North Carolina

Raleigh Women’s prison (male guard charged with repeated rape)Ohio

Marysville Women’s Prison ($525,000 lawsuit for rape)

Reformatory for Women (sexual abuse, cover-up)

Rape of women prisoners ‘rampant’Oklahoma

Department of Corrections (knowingly sent women to be sexually abused by a work-release program instructor in order to receive kickbacks)Oregon

Coffee Creek Women’s Prison (sexual assaults, cover-up)Pennsylvania

Lackawanna County Prison (systemic abuse)South Carolina

SC Department of Corrections (systemic abuse)