The Censorship of Chinese Feminists Mimics Western Trends

Feminist accounts removed from Weibo and Douban

This introductory article was originally published on Feminist Current.

On April 12, the Chinese government removed radical feminist groups from a popular social networking website called Douban. Similar to Reddit — which banned feminist groups critical of gender ideology last year — Douban is an online forum with a group function allowing users to post on various topics and engage in discussions. Of the groups deleted, several were centered on facets of the “6B4T” movement. Additionally, the term 6B4T was censored, and Douban users are not permitted to mention the names of the disappeared groups without risking suspension.

The abbreviation “6B4T” is a Chinese radical feminist movement that encourages women to reject sexual intercourse with men, as well as child-rearing, dating, and marriage. The ideology originated in South Korea and is associated with separatist feminism and political lesbianism, which advocates women organizing for their rights by refusing any participation with men and patriarchal institutions.

6B refers to six “no’s” regarding interactions with men: no sex, no marriage, no pregnancy, no dating, no purchasing from brands deemed to be supporting misogyny, and no cooperation with married women. The 4T’s are derived from the Korean word “tal,” which means “removal” or to “take off,” as seen in the South Korean “tal corset” movement, which advocates avoiding feminine trappings. This includes refusing to conform to patriarchal beauty standards, rejecting male-centered religions, and shunning aspects of culture that are perceived as promoting misogyny, such as pop music idols, anime, and video games.

In response to the deletion of the Douban groups, many women shared messages of support on Twitter and the hashtag, translated to, “women stick together,” sprung up on Weibo (China’s equivalent of Twitter), where it garnered over 50 million views. Twitter user @dualvectorfoil called the censorship “a devastating blow” to Chinese feminists in a thread that received replies from women around the world.

Women’s rights advocate Zhou Xiaoxuan, who fuelled China’s #MeToo movement when she filed a sexual assault suit against a well-known TV news anchor in 2018, expressed solidarity with the banned feminists on social media, saying, “I firmly support my sisters on Douban, and oppose Douban’s cancellation of feminist channels.”

According to journalist Sui-Lee Wee, writing for The New York Times, the recent spate of bans is not an isolated incident, but a pattern across Chinese social media platforms. On the popular forum Weibo, an account affiliated with the company’s chief executive, Wang Gofei, entered a conversation thread regarding tactics for reporting women who shared feminist views, instructing users to file complaints under “inciting hatred” and “gender discrimination.”

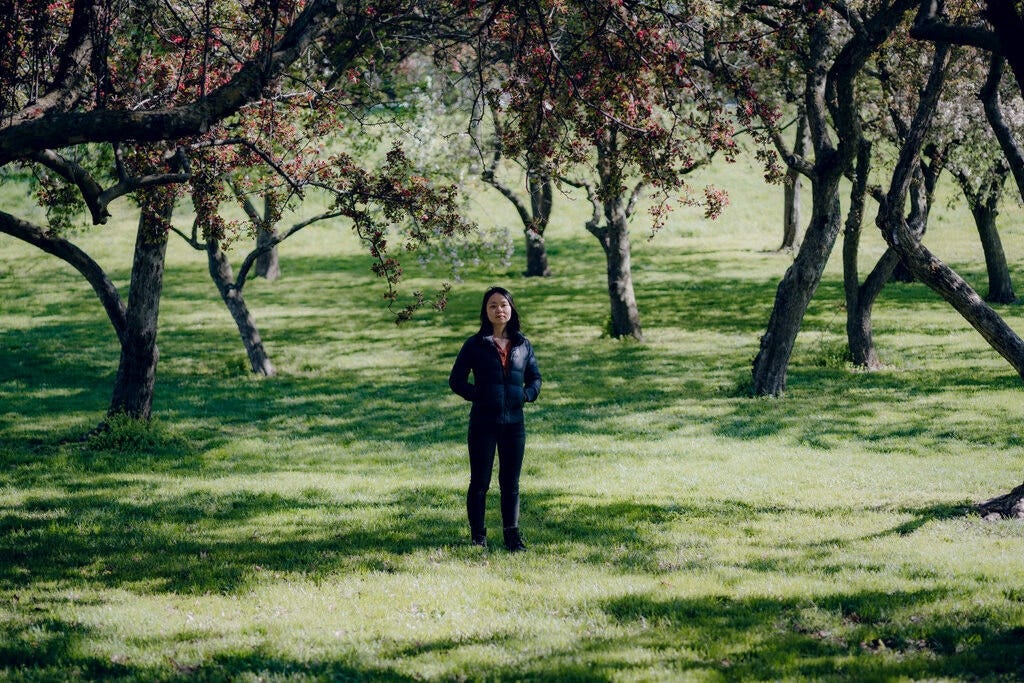

Wee points out that, in addition, several prominent Chinese feminists have had their accounts deleted from Weibo in recent weeks — at least 20 accounts as of this writing have been removed from the site. Among the women censored are prominent women’s rights campaigners like Liang Xiaowen, Zeng Churan, and Xiao Meili. Liang, an outspoken feminist and lawyer, said she was suspended for “gender discrimination” and is in the process of suing the company on the basis that the ban without adequate justification violates China’s civil code.

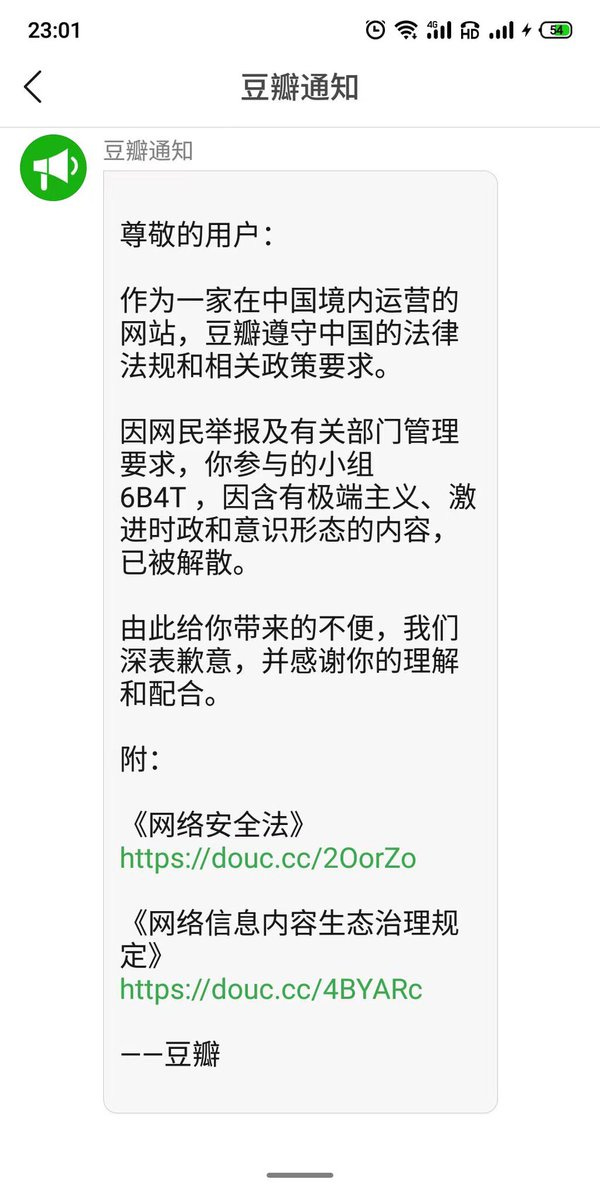

The reason for the removal of the radical feminist groups on Douban is not explicitly stated, but it is suggested that the ideas discussed in the forums violated national policies. The Twitter account FreeChineseFeminists (@FeministChina) shared a screenshot of a notification from Douban which told administrators of the banned groups that the forums contained “extremism, radical politics, and ideologies.” The uncompromising anti-marriage, anti-sex, and anti-birthing views asserted in the groups contradict government measures aimed at elevating current declining birth rates — now at their lowest since 1949. Kailing Xie, a researcher on gender and politics at the University of Warwick, told Vice, “China’s governing model is still pretty much relying on heterosexual marriages as the stabilizer. These feminist groups, especially the ones against marriage, against childbirth, are touching the nerves of the fundamental governing structure.”

Moreover, China has a severe sex-ratio imbalance due to female infanticides that resulted from a strict one-child policy and a patriarchal preference for male children. The restriction was in place for 35 years and ended in 2016; estimates place the number of girls aborted or killed after birth at anywhere between 30-60 million. Today, Chinese men outnumber women in the country by more than 30 million, according to census data. An international industry of bride trafficking has developed as demand for women has soared; China’s oppressive practices are resulting in the importation of women from nearby nations to fulfill men’s sexual entitlement. Women and girls are abducted from neighboring countries, bought from family members, or lured with promises of work. They are then sold for between $3,000 and $13,000 to men who marry them and hold them prisoner. The victims, who include underage girls, are repeatedly raped and forcibly impregnated by the men who buy them. They may also be sold into the sex trafficking industry.

A 2019 Human Rights Watch investigation identified victims from Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Pakistan, Nepal, and Vietnam. The numbers, when available, are startling: between 2013-2017, an estimated 21,000 women and girls from Myanmar were trafficked into a single province of China. According to a report from Korea Future Initiative, tens of thousands of North Korean women seeking to escape the Kim Jong-un regime are also abducted and sold into various forms of sex slavery in China. The business of the sale of North Korean women alone is estimated to be worth at least $105 million annually.

To make matters worse, a new law put in place in January makes it more difficult for women in China to file for divorce by requiring a 30-day “cooling-off period” before requests can be processed. The measure is aimed at preventing couples from separating as part of an initiative to increase the birth rate. In the eastern city of Hangzhou alone, more than 800 couples have been prevented from divorcing since its implementation, according to the local press. In a pattern mirrored throughout the world, domestic violence has escalated, though little has been done to address or prevent it. Violence against women is normalized through expressions such as “a beating shows intimacy and a scolding shows love,” and under the Confucianist principle of filial piety, women are expected to tolerate abuse without protesting.

Consequently, Chinese women in abusive households cannot rely on law enforcement to intervene on their behalf. The government implemented its first-ever law on domestic violence just five years ago, in 2016, as a result of public pressure and campaigning from women’s rights activists on social media and the All-China Women’s Federation. The law covers physical and psychological abuse but does not specifically outlaw sexual violence such as marital rape or economic coercion and applies only to married couples and cohabitating partners. It does not provide protections for women against former spouses or partners that do not reside together. A 2019 analysis of court cases found that victims were often unable to meet evidentiary requirements put forward by judges.

Such is the situation faced by women in China, who are being sent a clear signal that the government does not believe they have a right to discuss living their lives without men, or to entertain the notion of shunning marriage and childbirth. However, the censorship of women advocating feminist views that recognize women as a distinct sex class is not limited to China; rather, it is part of a global trend, a reality that Western media has thus far overlooked when reporting on the silencing of Chinese feminists.

Indeed, Western mainstream media and organizations claiming to support human rights advocate for the censorship of those who acknowledge women’s sex-based oppression. After several feminist subreddits were removed from Reddit last year, The Atlantic published an article comparing the forums to hate speech and referring to them as “toxic communities.” Both Target and Amazon have engaged in censorial practices aimed at critics of gender ideology, either by suspending the sale of books or by limiting their visibility — as in the case of Abigail Shrier’s Irreversible Damage and Ryan Anderson’s When Harry Became Sally — with relatively little pushback from major news outlets and the full support of organizations which claim to defend free speech. In November of last year, representative for the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) Chase Strangio, tweeted, “Abigail Shrier’s book is a dangerous polemic… Stopping the circulation of this book and these ideas is 100% a hill I will die on.” Grace Lavery, a professor of English at the University of California, Berkeley, who the aforementioned Atlantic piece sympathized with, tweeted, “I DO encourage followers to steal Abigail Shrier’s book and burn it on a pyre.”

In 2018, women’s rights advocate Meghan Murphy was banned from Twitter after referring to a predatory male as “he” — something countless critics of gender ideology have also experienced, including comedy writer Graham Linehan, as a result of the platform’s hate speech guidelines, which forbid the recognition of biological sex in favor of protecting a fabricated “gender identity.”

It is hypocritical of Western media to lament the censorship of feminists in China while promoting the very same tactics in the US, Canada, and elsewhere, in the name of gender ideology. The fact of the matter is that, regardless of nationality or justification, the discussion of the subjugation of the female sex by the male sex remains monitored and policed by those in power in an obvious attempt to maintain control over women and girls.

I spoke with an anonymous Chinese radical feminist (@dualvectorfoil) residing in New York about the censorship of feminists in China. Here is that interview.

Can you explain the ideas behind the 6B4T movement, and why you believe these groups were targeted for removal?

6B4T is a movement launched by radical feminists in Korea to help women prevent inevitable exploitation in heterosexual relationships and fight misogyny. B means “no” in Korean, so “6B” refers to six “Nos”:

1. No dating men

2. No sex with men

3. No marriage

4. No pregnancy

5. No purchasing from brands fueling misogyny

6. Anti-marriage women work together.

T is the abbreviation for the Korean word “Tal”, which means removal, so 4T is “four removals”:

1. Reject patriarchal beauty standards

2. Reject male-centered religions

3. Reject male pop idols

4. Reject anime, manga and games.

Some Chinese radical feminists translated and introduced those views on social media. 6B4T provoked a backlash from men and liberal feminists, who called them Nazis. However, Chinese radical feminists readily welcomed those ideas, because they had realized it’s impossible for women to not be taken advantage of by their male partners under patriarchy. They see this from endless femicide and rape in the news, extraordinarily lenient sentences for men who kill or assault women (even when the victims are minors), women contracting sexually transmitted diseases from men, contrasting social attitudes toward a woman’s and a man’s infidelity, and men secretly videotaping sex with women and posting those videos online.

As an example, a month ago, news broke out on China’s social media that Chinese men working in the San Francisco Bay area are sharing secret tapings of their sex partners and buying prostitutes on a Telegram group. Chinese women named the crime the Nth room case in Bay Area (a reference to a similar scandal in South Korea). So, you can tell the environment doesn’t seem to rectify Chinese men’s predatory behaviors.

Having known those facts, a rational woman will arrive at the obvious conclusion that women will lead a safer and healthier life without men. That’s why Chinese radical feminists view 6B4T as a detailed guidance on navigating male dominance and exploitation. Because 6B4T calls for women to shift their focus of attention and energy from men to women, we also consider it an effective way to resist the patriarchal oppression.

Unsurprisingly, these views threaten men. Male sexual entitlement seems as normal as a person needs eating and drinking, so how can men accept that women suddenly begin to reject them, and are asking other women to do the same? Hence, they attack, harass, and doxx feminists, especially those who embrace 6B4T. Before the government banned feminist groups on Douban, men had been mass reporting those groups and accusing them of “inciting sex-based antagonism”. I believe gender critical feminists in the West have encountered a similar situation.

Additionally, marriage has historically served the purposes for social stability and procreation. China has a severe sex-ratio imbalance due to sex-selective abortions and female infanticides. Chinese men outnumber women by over 30 million. This certainly doesn’t bode well for a society’s future, because men, especially “leftover” men, are prone to crimes and unrest. We believe the government can achieve at least three aims by coercing women into marriage: First, it reduces the number of “leftover” men and safeguards social stability. Second, marriage prompts women to pass up career opportunities, because of their extra sexual, emotional, and reproductive labors in marriage. This benefits men in securing employment, and as a result, further lowers the risk of social turmoil. Third, marriage is essential to combat China’s shrinking and aging population. Therefore, the government’s decision to remove those radical feminist groups is actually predictable. I believe many feminists more or less anticipated this outcome, but even so, when that day finally came, it’s still shocking.

The removal of those feminist groups happened against the backdrop of China’s looming census results. China’s National Bureau of Statistics had planned to release the once-in-a-decade census results in early April. After weeks of delay, on May 11th, they finally issued its census data, revealing the slowest population growth in decades and a falling birth rate. The male-to-female ratio at birth, is 111.3, and men outnumber women by 35 million. This doesn’t look very terrible. However, if you take into account the census data as of 2010 that 230 million Chinese citizens were born between 1960 and 1970, and combine that with the latest data that 890 million population aged 15 to 59, and over 300 million women aged 15 to 49, you’ll extrapolate that there can be as many as 70 million men than women in the age group of 15 to 49 years. Anyway, China’s statisticians are notorious for fiddling their figures. An economics professor at Peking University predicted that without strong policy intervention, China’s fertility rate will continue to drop in the coming years, and may become the world’s lowest. Women speculated that because of the census result, the government is not prepared to tolerate the uncompromising anti-marriage and anti-birthing radical feminists any longer.

Have other Chinese feminists been censored or banned from social media forums?

The short answer is yes. Chinese feminists have been constantly censored, and banned now and then. Some feminists were even banned across all Chinese social media platforms, and had to open accounts on Twitter and other foreign websites, which, unfortunately, are blocked in mainland China. For instance, in early April, one feminist’s social media account was permanently suspended because on the Tomb-Sweeping Day, she wrote a blog post, mourning for China’s 40 million “missing girls.” So, you can never be confident that you’re not crossing the red line.

To some extent, we get used to witnessing feminists being censored or reported, and are voluntarily self-censoring the content we post online. Censorship is omnipresent in China over all media, from book publishing to instant messaging. In the West, Twitter is notorious for banning gender critical accounts, but women can establish their own platforms like Spinster. This is out of the question for feminists in China because of the pervasive and sophisticated internet censorship.

What are some of the challenges faced by women in China? For example, can you explain some of the ways sexism is reflected in Chinese society?

I’d like to discuss three challenges here.

First, female infanticide has persisted in China for over two thousand years, and sex-selective abortion became rampant with the advent of ultrasound technology. The son preference is so ingrained in the culture that Chinese immigrants to Western high-income countries still perpetuate the practice. In 2018, a team of Australian researchers investigated this phenomenon and published their study in The International Journal of Epidemiology. I’ll quote their results here: “Compared with the naturally occurring M/F ratio, there was an increased ratio of male births to mothers born in India, China and South-East Asia, particularly at higher parities. The most male-biased sex ratios were found among multiple births to Indian-born mothers, and parity of two or more births to Indian and Chinese-born mothers.” Actually, after China eased its one-child policy around 2007, we observed the same pattern in the country’s sex-ratio. According to the census data in 2010, the sex ratio at birth is 114 for 1st parity births, but reached 130 and 162 for 2nd and 3rd parity births, respectively. In Beijing, the sex ratio for 3rd parity births reached 260. So, sex-selective abortion must be going on behind the scene.

Second, Chinese parents are more willing to invest in their sons in terms of educational expenditures as well as emotional support, and leave their son a majority of their estate, because the son carries on the family lineage. If a woman has a brother, usually she is destined to lose the competition with him for parental investment, and is expected to support her brother in a way that sacrifices her own welfare. Those sisters are groomed to prioritize their brothers’ interests. That’s why many singleton daughters born in the 80s and 90s think they fortuitously benefited from the controversial one-child policy, because those women received undivided and unprecedented family support, attention and investment. An economist at LSE once noted in a talk that an unintended consequence of the one-child policy is that it closes the gap of higher education attainment rate between girls and boys, and the returns to schooling for girls are now actually higher than that for boys in China. Still, those benefits are transitory. The fundamental issue of son preference underlying women’s plight has never gone away.

Third, Chinese women are losing out in the workforce. A lot of job descriptions state that only men need apply or men are preferred, barring women or discouraging them from applying. It’s normal for hiring managers to inquire about a female candidate’s marital status and pregnancy plans in a job interview. On paper, China’s labor law protects women’s maternity rights by requiring employers to provide paid maternity leave at their own expense. In practice, it increases the potential cost of hiring women. If a woman is considering having children in a few years, she will very likely not gain employment or promotions. Additionally, employers harbor the misgivings that women are hardly able to be dedicated workers or will eventually leave full-time employment for childrearing. Their suspicions are not wholly unfounded. Yet nowadays, even a female applicant explicit about no childbearing in the near future will miss out on career opportunities because employers are averse to hiring women to avoid associated risks altogether. The end of the one-child policy aggravates the situation. Previously, employers would give the green light to a female applicant who’s married with a child, but not anymore. When it comes to university admission, women increasingly must score higher than men in the nationwide university entrance exam to get in universities. The bars for women and men can differ by 40 points. The practice is especially entrenched at police or military-affiliated universities.

Other challenges facing women in China include the high level of femicide and sexual violence. News of men killing women in broad daylight comes in every week. I’ll not go into detail about this, but these cases are not only husbands murdering their wives, but men stabbing female strangers to death on busy streets. A Chinese feminist has been documenting femicide and rape news on Github to avoid China’s censorship, but this doesn’t stop Chinese men from reporting her on the website. The rampant male violence against women is a reason that separatism is a key topic in our feminist discussions.

In addition, it’s alarming that most young Chinese have no issue with transgenderism, or the myth that trans-identified males are as well oppressed by patriarchy. South Korean radical feminists have a far more thorough understanding of the trans issue, partly thanks to the fact that they translated and published Sheila Jeffreys’s books and journal articles. Currently, we see very few radical feminist books published in China. Honestly, the only one I can think of is The Second Sex by Simone De Beauvoir. Yet Sally Hines’ transgender-pandering book has been published into Chinese last year. Although China is a conservative country, transgenderism has taken root in young people’s mind.

You had mentioned that gender ideology seems to be taking hold in China among the younger generation. Can you explain a little more about that?

I believe transgenderism is taking hold in young people. We have a famous transsexual dancer who’s recognized by public as a woman, so transgenderism is not really a new concept to Chinese people. Thankfully, we don’t yet have legislation that allow men to enter female-only spaces, but I know there are quite a few trans-identified males using women’s bathrooms, and justify it by saying this corresponds with their gender identity. This instigated a heated debate in 2020. Most women sympathize with trans people, thinking they’re oppressed by patriarchy, and accusing radical feminists of not supporting those minority groups. Some women think it’s okay for men to enter women’s bathrooms if he’s undergone the sex reassignment surgery.

They are doing the same thing on China’s social media. Women who say trans-identified males are men are getting called TERFs. Some feminists sometimes post gender critical content online, and this will always provoke ire from queer activists. Yes, queer theory is also very popular among young generations in China. It’s also common for liberal feminists accuse gender critical feminists of adopting ideas from privileged white, although I don’t know what that means, because most liberal feminists online are studying abroad or have studied abroad. Liberals in China welcome western ideas, and queer theory is seen as a progressive ideology, so most young people embrace it.

In your view, is feminism becoming more discussed in China?

Feminist awareness has certainly increased over the years, and feminism has moved from a niche community to mainstream, at least on female-dominated online forums. Before 2015, it was exceedingly rare to meet anybody discussing feminism online. Even if someone did, she would draw ridicule because of the deeply entrenched sex stereotypes in society. Feminist consciousness raising in China relies largely on social media. Thanks to persistent feminist discourse of a handful of female bloggers, over the years, feminist voices have grown louder on Weibo, which is the Twitter counterpart in China, as well as Douban, which used to be a gathering place for Chinese feminists. Initially, feminist discussions centered on anti-marriage, anti-pregnancy and anti-surrogacy. These views gradually became the fundamentals for Chinese feminists, and more women started to realize the risks to women in heterosexual relationships, like male violence, the PIV-as-sex paradigm, and STDs. Naturally, this led to the question: if marriage perpetuates male privilege and is detrimental to women, why should we appreciate dating and loving men? 6B4T thus became a wise choice. Other feminist topics include experiments with a matrilineal descent system, such as passing mothers’ surnames to their children, and single women’s appeal for easy access to assisted reproductive services.

However, those feminist discussions remain limited to cyberspace, and the participants are predominantly young women, usually under 30. Take me as an example, when I expressed radical feminist and separatist views with my mother, she said I was out of my mind.

Are there any other outlets for feminist organizing being created?

Feminist discussions have taken place only online, and are held by independent feminist accounts. I doubt there’s going to be any radical feminist organizing in the short term, because any organizing or peaceful assembly in China requires authorization from the Chinese Communist Party. The CCP has endorsed a few women’s rights campaigns, like donating money or sanitary pads to help girls from poor and marginalized communities. Yet compared with the recurring waves of crackdowns on feminism, those seem like perfunctory support, and plenty of money or goods donated didn’t end up going to the girls in need. This is especially the case when a girl has a brother.

How can women internationally support feminists in China?

I’ve brought this question to other Chinese feminists. Unfortunately, none of us could think of a satisfactory answer. The Great Firewall and sophisticated censorship ruled out almost any possibility. In addition, one of Chinese men’s ploys to attack feminists is to accuse us of colluding with foreign countries or with external elements to endanger the nation. Admittedly, it’s a nonsensical accusation, but this further hinders communication between feminists in China and in other countries.

That's a really interesting interview. I had not know of the recent legal changes, nor the results of the latest census. Great stuff here!